Explainer: why Wesfarmers is ditching Coles

- Written by Gary Mortimer, Associate Professor in Marketing and International Business, Queensland University of Technology

Coles will soon be an independent company again, with more than 800 supermarkets, nearly 900 liquor stores, 700 service stations, and 88 hotels.

Spinning off Coles is a great example of how good Wesfarmers is at entering and exiting markets. Buying the ailing Coles in 2007 was a smart move.

But the supermarket sector has changed dramatically in the past decade in relation to intense competition, with the growth of discounters like Aldi and the emergence of price-conscious shoppers who simply shop across multiple brands of supermarket each week.

Customers have benefited from price deflation, but it is a different story for suppliers.

The nature of these relationships has regularly been criticised and investigated.

A new owner will bring these matters back to the forefront. Ultimately, private equity firms and global businesses only purchase companies and enter markets where considerable return on investments can be made.

Read more: Why Australian supermarkets continue to look to the UK for leadership

Cash cows and dogs

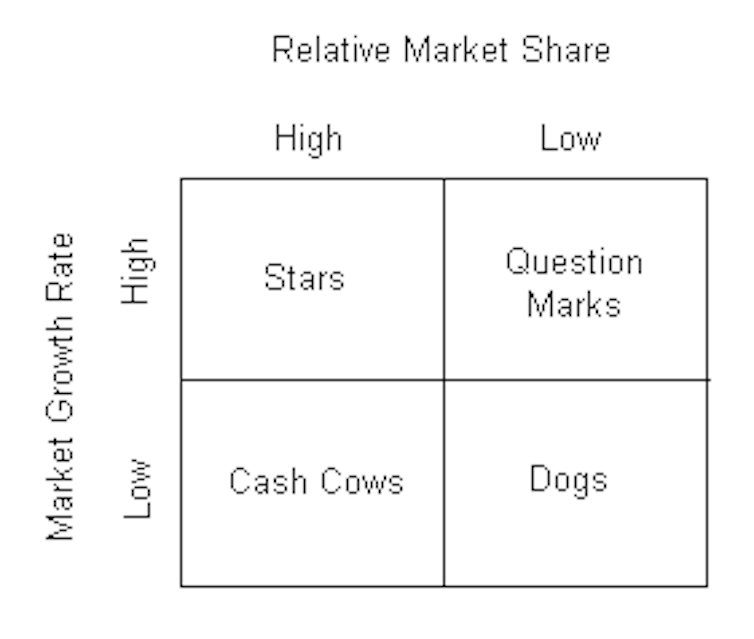

Most first-year business students deal with these conundrums and often rely on simple models like the classic Boston Consulting Group’s Matrix.

Boston Consulting Group’s growth share matrix.

CC BY

Boston Consulting Group’s growth share matrix.

CC BY

Businesses move around in these quadrants, depending upon external, macro-level impacts. A stronger Kmart will push Target from a “Star” into the “Dog” category very quickly.

Wesfarmers has successfully moved Coles from “Dog” status 10 years ago to “Cash Cow”, but profits have slid in recent years.

Coles also accounts for a staggering 61% of the capital deployed in Wesfarmers’ entire portfolio (which includes other retail brands, industrial, mining and energy businesses), but contributes just 34% of earnings before interest and tax.

The supermarket sector has seen a huge increase in competition in recent years, with the growth of discounters like Aldi. There is also a possibility of more international competition from the German discounters Kaufland and Lidl.

This month, Fred Harrison, chief executive of Ritchies, Australia’s largest chain of independent supermarkets, called for an end to the “price wars”. Metcash, a wholesaler for independent supermarkets, recently delivered a loss in its food and grocery business.

Coles itself has signalled a move away from its strategy of slashing prices.

Read more: Down, down but not different: Australia's supermarkets in a race to the bottom

Other than putting cash back on Wesfarmers’ balance sheet, spinning off Coles creates two long-term revenue streams for Wesfarmers.

To begin with, Wesfarmers will aim to a hold 20% stake in Coles. So some profits will continue to flow back to Wesfarmers.

More importantly, Wesfarmers intends to retain “substantial” ownership in Flybuys, Coles’ loyalty program.

The value of loyalty programs is best highlighted by Woolworths’ purchase of Quantium in 2013 for almost A$20 million.

These programs hold a vast amount of data, giving Wesfarmers huge customer analytics capabilities with which to tailor promotions, product ranges and store layouts across all of its other retail businesses.

The new owners of Coles will also be eager to access this data.

Who will buy Coles?

While Wesfarmers will remain a minor shareholder, there will be plenty of interest in the majority share among private equity investors and international players (such as Walmart and Carrefour).

Walmart entered Canada through an acquisition, Mexico through a 50-50 joint venture with Cifra (Mexico’s largest retailer), and Brazil through a joint 60-40 (in favour of Walmart) with Lojas Americana.

Likewise, French retail giant Carrefour has adopted a range of approaches to international expansion, including joint ventures and acquisitions.

Read more: Can Coles (Fly) buy shopper loyalty?

Ultimately, private equity investors and global businesses will only buy companies and enter markets where they can make a considerable return on investment.

Considering the declining margins in supermarkets, driven by low-cost operators like Aldi, it is likely that this will be done by squeezing suppliers.

On the other hand, a new Coles will no longer be constrained by Wesfarmers’ conglomerate ownership model. One of the challenges faced by large conglomerates is “strategic inertia”.

A separate business will lead to faster innovation, greater investment and potentially another battle for market share between Australia’s two big supermarkets.

Source http://theconversation.com/explainer-why-wesfarmers-is-ditching-coles-93482