Smart money: a better way for Australia to select big transport infrastructure projects

- Written by Marion Terrill, Transport Program Director, Grattan Institute

Australia needs to change the way it assesses potential infrastructure projects, to ensure that governments can better understand which road and rail projects are worth building.

One way would be to make long-overdue changes to how we value the impact of infrastructure on future generations. This is done through the choice of a “discount rate” – the mechanism used to compare costs and benefits of projects that occur at different points in time.

Australian governments have chosen to keep their central discount rate at 7% since at least 1989. This is despite one of the key components of the discount rate, the real borrowing rate, varying from as high as 8% to below 1% in this time.

The latest report released by the Grattan Institute recommends that governments adopt discount rates that change when the world changes, and that reflect the riskiness of a project.

While the concept might seem arcane, using an artificially high discount rate muffles the signal that tells governments what projects are worth building and which ones aren’t. Using the wrong discount rate probably means we build the wrong infrastructure.

Costs and benefits

A future benefit or cost needs to be converted into today’s dollars because future dollars have a different value to today’s dollars. This is because, even ignoring the effects of inflation, people value a dollar today more than one at some future date.

When a transport project’s benefits mostly come about in the distant future, a high discount rate treats those benefits more sceptically than a low discount rate would.

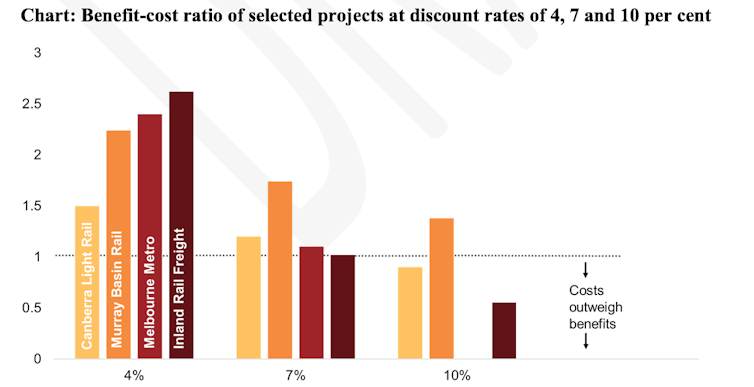

The Melbourne Metro rail project provides a good example of the discount rate’s importance. If we use a 7% discount rate, as recommended by Infrastructure Australia, the estimated benefits are only a tiny 10% larger than the costs.

But using a 4% discount rate, the project will deliver benefits that are almost two-and-a-half times greater than the project’s A$9 billion cost.

On one reading, then, the project is expected to be a major economic success. On another its value is marginal. Changing the discount rate has huge implications for the cost-benefit analysis of new projects.

The discount rate is also an important determinant of the mix of projects that governments consider. As you can see in the chart below, changing the discount rate changes the rankings of different projects.

Author provided

Re-examining the basis for Australia’s discount rates

Discount rates are part of the appraisal and ranking of potential infrastructure projects. The discount rate is designed to reflect the next-best use of the resources for that project, and with the same level of risk.

The next-best project could be another project in the transport portfolio, in another portfolio, or even a financial investment overseas with the same level of risk.

Our report challenges the way Australian governments apply this framework. Instead of being frozen at 7%, discount rates should vary when there is material variation in the cost of money. In addition, discount rates should differentiate between projects that are more risky and those that are less risky. If we are comparing a low-risk project with a riskier one, then we’re comparing apples with oranges.

The cost of money is usually inferred from government borrowing costs, signalled by the 10-year Commonwealth bond rate. Back in 1989, when the 7% discount rate was established in Australia, the government borrowing rate was 6.8% in real terms (adjusted for inflation); in 2017, it was 0.8%.

Discount rates should reflect such a dramatic change in the cost of money.

The type of risk that matters for discounting is the sensitivity of a project’s expected returns to the economy generally – known as the systematic risk.

Most government transport infrastructure is still used whether the economy is booming or in the doldrums, because most people keep on travelling to work or school and buying transported goods. But some projects are more sensitive than others to the state of the economy, and the discount rate should be higher for them.

If we incorporate risk and the cost of low-risk borrowing, the discount rate in 2018 should be around 3.5% for projects where systematic risk is low, and around 5% where it is high by the standards of transport infrastructure projects.

Both rates are substantially below today’s 7% standard central rate. Sensitivity testing remains important, of course, because precision is difficult.

Better evaluations

Lower discount rates will help to make clear which are the most valuable transport projects available. But they will also make the economics of all transport projects look better.

Our recommendations may therefore seem at odds with previous Grattan Institute analysis, which showed that Australian governments have systematically underestimated the cost of transport projects, making many appear more attractive than they really were.

But our consistent goal is to improve all aspects of project selection and appraisal, so we can know which are the best projects to build and in what order. This accords with past work by both the Productivity Commission and Bureau of Transport, Infrastructure and Regional Economics, arguing that the discount rate is not the appropriate way to deal with optimism bias.

Ultimately, using an artificially high discount rate comes at the cost of distorting public policy priorities. We should be aiming to improve every aspect of evaluation wherever better approaches are evident, so we build the right projects in the right order. Better discounting would be a big step in that direction.

Author provided

Re-examining the basis for Australia’s discount rates

Discount rates are part of the appraisal and ranking of potential infrastructure projects. The discount rate is designed to reflect the next-best use of the resources for that project, and with the same level of risk.

The next-best project could be another project in the transport portfolio, in another portfolio, or even a financial investment overseas with the same level of risk.

Our report challenges the way Australian governments apply this framework. Instead of being frozen at 7%, discount rates should vary when there is material variation in the cost of money. In addition, discount rates should differentiate between projects that are more risky and those that are less risky. If we are comparing a low-risk project with a riskier one, then we’re comparing apples with oranges.

The cost of money is usually inferred from government borrowing costs, signalled by the 10-year Commonwealth bond rate. Back in 1989, when the 7% discount rate was established in Australia, the government borrowing rate was 6.8% in real terms (adjusted for inflation); in 2017, it was 0.8%.

Discount rates should reflect such a dramatic change in the cost of money.

The type of risk that matters for discounting is the sensitivity of a project’s expected returns to the economy generally – known as the systematic risk.

Most government transport infrastructure is still used whether the economy is booming or in the doldrums, because most people keep on travelling to work or school and buying transported goods. But some projects are more sensitive than others to the state of the economy, and the discount rate should be higher for them.

If we incorporate risk and the cost of low-risk borrowing, the discount rate in 2018 should be around 3.5% for projects where systematic risk is low, and around 5% where it is high by the standards of transport infrastructure projects.

Both rates are substantially below today’s 7% standard central rate. Sensitivity testing remains important, of course, because precision is difficult.

Better evaluations

Lower discount rates will help to make clear which are the most valuable transport projects available. But they will also make the economics of all transport projects look better.

Our recommendations may therefore seem at odds with previous Grattan Institute analysis, which showed that Australian governments have systematically underestimated the cost of transport projects, making many appear more attractive than they really were.

But our consistent goal is to improve all aspects of project selection and appraisal, so we can know which are the best projects to build and in what order. This accords with past work by both the Productivity Commission and Bureau of Transport, Infrastructure and Regional Economics, arguing that the discount rate is not the appropriate way to deal with optimism bias.

Ultimately, using an artificially high discount rate comes at the cost of distorting public policy priorities. We should be aiming to improve every aspect of evaluation wherever better approaches are evident, so we build the right projects in the right order. Better discounting would be a big step in that direction.