The Cabinet Files show that we need to change the nature of record-keeping

- Written by Paula Dootson, Research Fellow in the Chair in Digital Economy, Queensland University of Technology

Punishing the person or persons responsible for this week’s Cabinet Files leak does not address the underlying issue. The real problem is that the way governments and businesses keep records is broken.

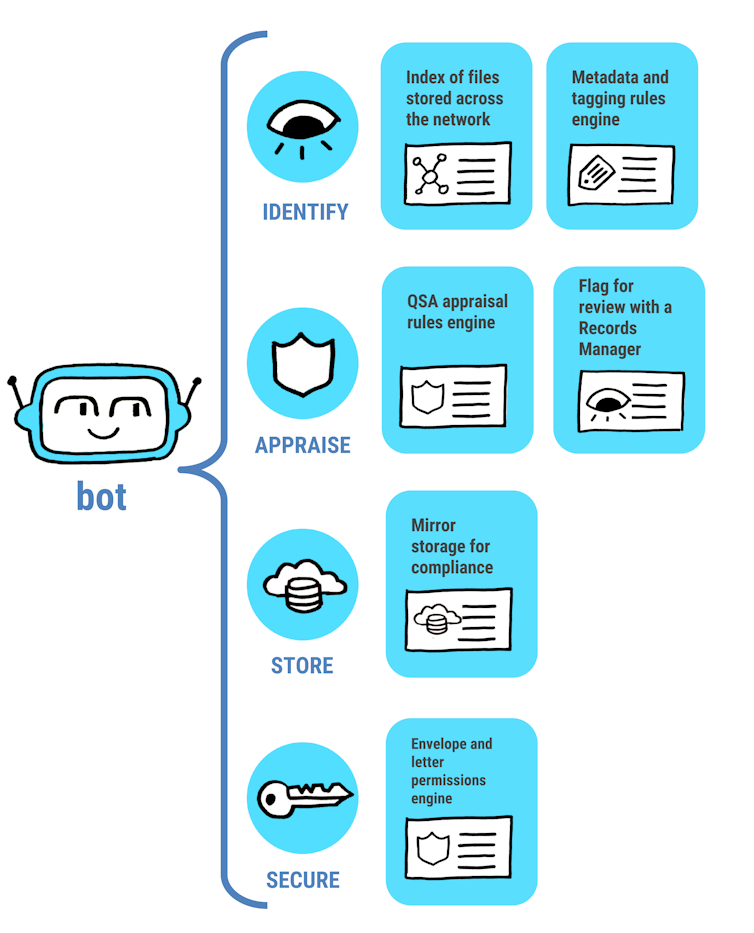

Recently, we collaborated with Queensland State Archives to design a bot to automatically identify, appraise, store, and secure their records. No human intervention, or compliance, is required.

This kind of system is called “compliant-by-default”, and it is just one way we can re-imagine record-keeping to address low levels of compliance in our organisations.

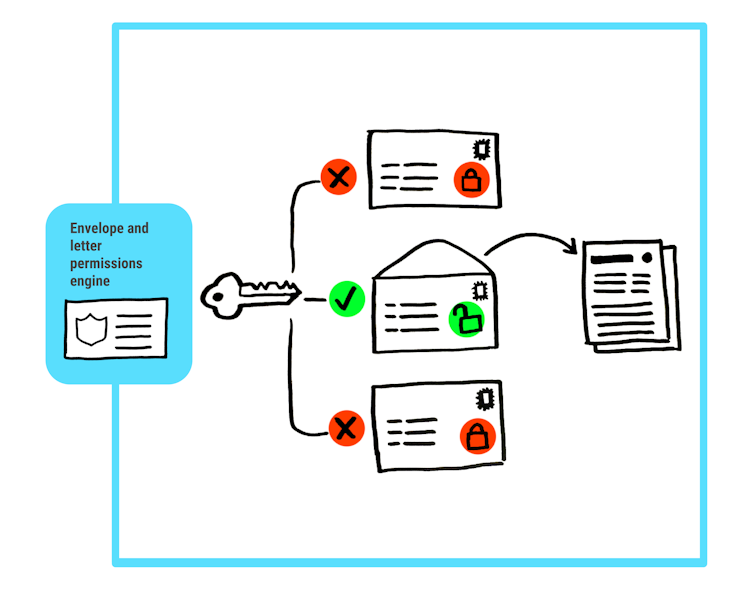

A compliant-by-default system manages issues of security and restricted access by ensuring that only people with appropriate permission can see the contents of a record, while others are still allowed to see that the record exists, alongside high-level attributes of what the record contains.

This is essentially the difference between seeing the outside of an envelope versus its contents. The information written on the envelope is public, to aid in searching data, while the contents of the envelope are private.

Bot: Security and permissions logic.

Bot: Security and permissions logic.

The federal government’s current record-keeping system relies on employees fully understanding all the rules and standards associated with creating, storing, managing, preserving, and destroying records. Getting this right 100% of the time is not only improbable, but is unnecessary when it could be automated.

But it’s not just in government that record-keeping needs updating. A recent report found that in Western Europe, 57% of office workers spend an hour or more a day looking for missing documents.

This is the most basic example of a broken record-keeping system.

From record-keeping to record-using

The cabinet files were published by the ABC because there is an appetite for transparency around political decision-making.

But how many of us actually go and search the records that are already available? There is an opportunity here to re-imagine the way government agencies keep records, so that they not only become more usable, but more accessible for the public as well.

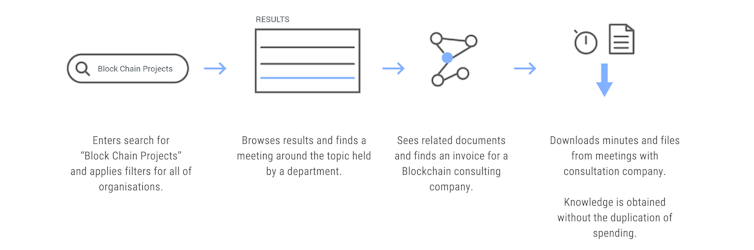

For instance, if someone inside an organisation starts a project with blockchains, a system like ours would make it easier to search and connect with other teams working on similar projects. This would not only allow for more collaboration, but give better transparency through the organisation and avoid duplicate spending (taxpayer money or private funds).

Record-using: gaining context surrounding a record.

Record-using: gaining context surrounding a record.

This also has the potential to unlock new revenue streams, by using the records to provide services that were not previously possible. This is similar to how the advent of MP3 technology and high-speed internet made it possible to buy and store music libraries online.

The process of record-keeping could be monetised by mining the archival data, to look for efficiency gains in business processes, for example, or sell business insights to the public and private sector.

The digital vs physical debate

While the general perception may be that physical records are easier to secure and manage, the reality shows that this is not the case. There are finite possibilities of what can go wrong with digital - copy, hack, share - but there is always a trace.

With physical records, there are infinite possibilities of things that can go wrong, and no way to trace it. There is no way to know what is being photocopied, if a record leaves a building, or who has the key to the cabinet.

While the sheer scale of potential attacks on a digital storage system may be much higher, a well-designed digital system can be protected.

It would be absolutely fine to print the records that need to be printed for the time they are needed. Systems should be designed to allow individuals to work in the way they prefer to work. Such a “digital first” approach is now being championed by the Queensland Government in its recent strategy.

Bot: a compliant-by-default recordkeeping concept.

Bot: a compliant-by-default recordkeeping concept.

The Cabinet Files story is not about who lost the key, or who sold the cabinet. It is about why these papers existed, were in a filing cabinet, and how such a range of documents ended up together.

The need for fundamental record keeping reform is imminent.

If we must continue keeping records, then digital records offer new value to both government and business. Archival agencies have an opportunity to redefine what record keeping means to people and why it’s important, and to turn it from a chore to a superpower, from a back-end operation to front-facing business intelligence.

A digital record isn’t something to be locked away in an archive, it is the currency of knowledge transfer. What is unique about this solution is that we are not looking to make humans more compliant, rather, to making the system compliant-by-default.