Clive Palmer versus (Western) Australia. He could survive a High Court loss if his company is found to be “foreign”

- Written by Luke Nottage, Professor, Sydney Law School, University of Sydney

We may not like Clive Palmer as a person, or his business activities, or his politics, but from a legal perspective that should not matter.

All of us, rich or poor, should have equal rights under the rule of law, including access to independent review mechanisms.

So we should be concerned in principle about the oddly-named Iron Ore Processing (Mineralogy Pty. Ltd.) Agreement Amendment Act.

It was hastily passed by the Western Australian parliament on August 13 in order to legislate away Palmer’s rights under a contract with Western Australia regarding the Balmoral South mining project.

Former High Court judge Michael McHugh upheld those rights in 2014 and 2019 arbitration awards.

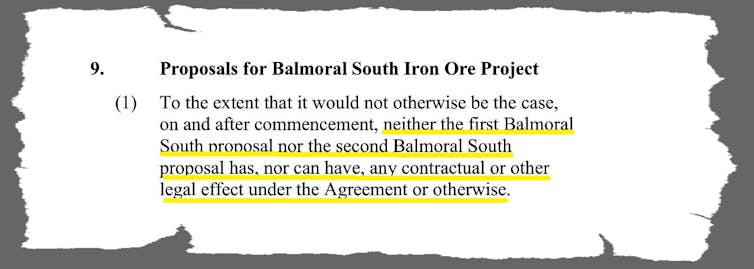

The Act declares the contract to have no effect (s9) and declares both arbitration awards to have no effect (s7).

It makes the contract’s arbitration clause “not valid” (s10).

It says Western Australia cannot be sued and has no liability in any project-related dispute (s11).

Iron Ore Processing (Mineralogy Pty. Ltd.) Agreement Amendment Act 2020

Rules of “natural justice” (including any duty of procedural fairness) are said not to apply to the West Australian government’s conduct, past or future (s12).

Palmer and associates must indemnify Western Australia against any loss connected with them including reduced funding from the Commonwealth (s14).

Read more:

The WA government legislated itself a win in its dispute with Clive Palmer — and put itself above the law

Palmer has challenged the statute under Australian law. There’s every chance the case will make it to the High Court.

But even that might not be the end of the matter.

He has also foreshadowed a challenge under international law of the kind allowed under several of Australia’s free trade agreements.

Palmer might say his company is foreign

He says his Balmoral South project is an investment made by Mineralogy International, registered in Singapore (and reportedly perhaps for this purpose), and so is protected under a free trade agreement.

Australia’s Free Trade Agreement with Singapore was signed in 2003 and amended in 2017 to refine its investor-state dispute settlement provisions bringing them into line with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, in force between Australia and six other nations including Singapore and also the so-called ASEAN+ treaty.

Provisions in such treaties allow foreign investors to seek compensation from Australia for acts of expropriation.

Foreigners get extra rights

They cover not only direct expropriation – where the government acquires property – as do similar provisions in the Australian Constitution, but also indirect expropriation, where a government prevents an investor from exercising property rights.

Australia has only once squarely faced the use of such provisions, after the High Court dismissed a challenge to its 2010 tobacco plain packaging legislation.

Iron Ore Processing (Mineralogy Pty. Ltd.) Agreement Amendment Act 2020

Rules of “natural justice” (including any duty of procedural fairness) are said not to apply to the West Australian government’s conduct, past or future (s12).

Palmer and associates must indemnify Western Australia against any loss connected with them including reduced funding from the Commonwealth (s14).

Read more:

The WA government legislated itself a win in its dispute with Clive Palmer — and put itself above the law

Palmer has challenged the statute under Australian law. There’s every chance the case will make it to the High Court.

But even that might not be the end of the matter.

He has also foreshadowed a challenge under international law of the kind allowed under several of Australia’s free trade agreements.

Palmer might say his company is foreign

He says his Balmoral South project is an investment made by Mineralogy International, registered in Singapore (and reportedly perhaps for this purpose), and so is protected under a free trade agreement.

Australia’s Free Trade Agreement with Singapore was signed in 2003 and amended in 2017 to refine its investor-state dispute settlement provisions bringing them into line with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, in force between Australia and six other nations including Singapore and also the so-called ASEAN+ treaty.

Provisions in such treaties allow foreign investors to seek compensation from Australia for acts of expropriation.

Foreigners get extra rights

They cover not only direct expropriation – where the government acquires property – as do similar provisions in the Australian Constitution, but also indirect expropriation, where a government prevents an investor from exercising property rights.

Australia has only once squarely faced the use of such provisions, after the High Court dismissed a challenge to its 2010 tobacco plain packaging legislation.

Philip Morris Asia’s use of a Hong Kong treaty was found to be an abuse of process.

Philip Morris Asia, a Hong Kong based company which took control of Philip Morris trademarks when Australia was preparing its plain packaging legislation, used a Hong Kong-Australia investment treaty to claim US$4.16 billion for indirect expropriation.

The arbitration tribunal dismissed that claim as an “abuse of process” under customary international law.

Philip Morris Asia was found to have obtained control of the trademarks in order to gain investment treaty protection when the dispute was foreseeable.

The Singapore-Australia Free Trade Agreement further commits Australia to providing the “customary international law minimum standard of treatment to foreigners”.

This “includes the obligation not to deny justice in criminal, civil or administrative adjudicatory proceedings in accordance with the principle of due process embodied in the principal legal systems of the world”.

Why promise additional rights to foreign investors?

Because domestic law may not meet international standards. The extension of such rights can encourage domestic investors press for better local standards.

Offering the global standard can also encourage more foreign direct investment.

Palmer might face problems…

If Mineralogy International does try to file an investor state dispute claim, it will have to establish that its investment is covered and that it is a foreign investor for the purpose of the treaty.

Australia might invoke a “denial of benefits” provision if Mineralogy International lacks substantial business activities in Singapore.

It might also allege “forum shopping” of the kind Philip Morris Asia was found to have engaged in.

…but those rights are important

This is how international law is supposed to work. As with human rights treaties, nations consent to international standards.

Impartial investor state dispute settlement procedures make a national commitments to investors credible. Exceptions acknowledge abuses of process.

If provisions generate problems, such as costs and delays, Australia can negotiate improvements and review and modernise old treaties.

It did that with the Hong Kong Australia treaty after the Philip Morris case and it has just committed to do it with the remaining older treaties.

An innovative way forward would be adding compulsory mediation before arbitration, as with the Australia-Indonesia Free Trade Agreement signed last year.

Philip Morris Asia’s use of a Hong Kong treaty was found to be an abuse of process.

Philip Morris Asia, a Hong Kong based company which took control of Philip Morris trademarks when Australia was preparing its plain packaging legislation, used a Hong Kong-Australia investment treaty to claim US$4.16 billion for indirect expropriation.

The arbitration tribunal dismissed that claim as an “abuse of process” under customary international law.

Philip Morris Asia was found to have obtained control of the trademarks in order to gain investment treaty protection when the dispute was foreseeable.

The Singapore-Australia Free Trade Agreement further commits Australia to providing the “customary international law minimum standard of treatment to foreigners”.

This “includes the obligation not to deny justice in criminal, civil or administrative adjudicatory proceedings in accordance with the principle of due process embodied in the principal legal systems of the world”.

Why promise additional rights to foreign investors?

Because domestic law may not meet international standards. The extension of such rights can encourage domestic investors press for better local standards.

Offering the global standard can also encourage more foreign direct investment.

Palmer might face problems…

If Mineralogy International does try to file an investor state dispute claim, it will have to establish that its investment is covered and that it is a foreign investor for the purpose of the treaty.

Australia might invoke a “denial of benefits” provision if Mineralogy International lacks substantial business activities in Singapore.

It might also allege “forum shopping” of the kind Philip Morris Asia was found to have engaged in.

…but those rights are important

This is how international law is supposed to work. As with human rights treaties, nations consent to international standards.

Impartial investor state dispute settlement procedures make a national commitments to investors credible. Exceptions acknowledge abuses of process.

If provisions generate problems, such as costs and delays, Australia can negotiate improvements and review and modernise old treaties.

It did that with the Hong Kong Australia treaty after the Philip Morris case and it has just committed to do it with the remaining older treaties.

An innovative way forward would be adding compulsory mediation before arbitration, as with the Australia-Indonesia Free Trade Agreement signed last year.